Skift Take

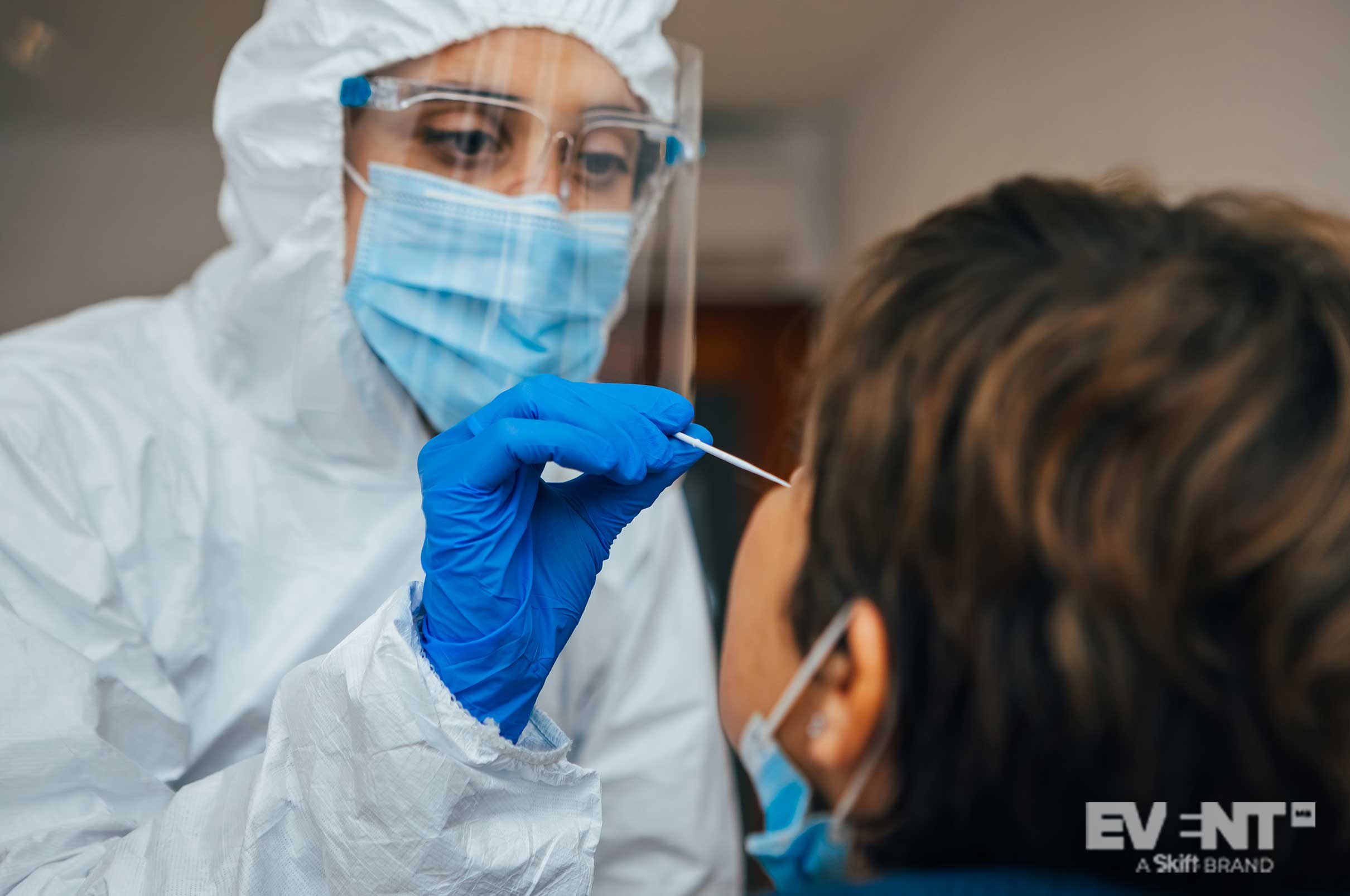

A February “Stronger Together” joint trade show in Orlando was the first of its kind to trial an onsite testing program. Then news broke about a cluster of infections related to a much smaller testing bubble on the other coast. So how reliable is testing?

Event professionals are grappling with government-imposed restrictions and the industry’s leaders are urgently making a case for permitting them in their lobbying and advocacy efforts. Part of this effort involves sponsored research studies designed to demonstrate the efficacy of testing — and part of it involves litmus testing as real events take place.

Determining exactly which factors are operative in an event’s safety success is a challenge, particularly when relying on studies that simulate ideal conditions and near-maximum compliance. As with vaccine testing, the real efficacy data comes from the latter, the real-world examples.

But how reliable is this data? How diligently is it being collected, and how transparently is it being shared? How much protection do testing initiatives really provide? And perhaps more to the point, how can we even know without deliberate and transparent follow-up testing?

This post takes a close look at the trade show’s safety measures and compares them against the conditions that caused a small outbreak following an event held in California’s Culver City — and how the public actually came to know about it.

Trade Show Employs Mass-Testing

Organized by Informa, Stronger Together gave fashion industry insiders the chance to meet in person and enjoy a tactile experience of new product lines. While the benefits of gathering in person may be undeniable, the potential risk of transmission is less clear.

How much protection did the event’s testing program provide?

Even though the event extended over three days, only one test was required to secure admission — and attendees had the option of doing it up to four days in advance. A four-day window is ample opportunity for transmission to occur, particularly with attendee numbers in the thousands. Steven Adelman, VP of the Event Safety Alliance, recently recommended doing both PCR pre-testing and onsite antigen testing, but the trade show had an either/or policy.

Nevertheless, the in-person trade show collaboratively organized for MAGIC, OFFPRICE, and WWIN is already being lauded as a success, attracting 40% more registrants than anticipated. A SISO newsletter recently announced plans to release a case study on how the event’s testing program was organized.

Follow-Up Testing Proves Event Bubbles Can Be Popped

Shortly before the Orlando trade show took place, a small number of elite executives met on the other side of the country for Abundance 360 (A360), another three-day event involving 84 participants including staff. Notably, the organizer is choosing to call the event a “Virtual Studio-broadcast production” because the gathering was held at a time when in-person events were strictly forbidden under California law.

Even given its unique circumstances, this event does provide some valuable lessons for event planners. Its dubious legality gave organizers every incentive to ensure it went off without incident, and its deep-pocketed attendees afforded it an ambitious three-tiered testing program. The event required:

-

- A lab-based PCR test done no more than 72 hours before the event

- BOTH a rapid PCR test and a lab-based PCR test conducted on arrival

- Daily tests thereafter (of an unspecified type, but likely antigen)

Despite extensive testing throughout the event, somewhere between 21 and 24 of the 84 participants (including staff) ended up testing positive for the virus shortly after.

What Went Wrong, And How Do We Know?

Testing is not a fool-proof solution. Not all PCR tests are equally accurate, and even the best among them can miss cases early in the infection period. Even with the best lab-based testing available, the National Women’s Hockey League recently had to cut its tournament short after over 20 percent of its players ended up contracting the virus.

Diamandis, the entrepreneur behind A360, thinks his biggest failing was allowing attendees to take off their masks because of the false sense of security provided by testing. Notably, none of the event’s 35-strong AV team tested positive, and all wore masks throughout the event.

For this reason, testing is meant to be taken as one component of a larger, multi-faceted program of risk mitigation, and Informa’s strategy reflected that. As could be expected, however, compliance was somewhat of an issue. News footage of the event reveals a general disregard for the six-foot rule along with several people wearing their masks below their noses, not to mention an attendee pulling her mask down to talk and another not wearing one at all.

Of course, these Covid safety measures are ultimately about risk reduction rather than risk elimination, but exactly what constitutes an acceptable level of risk is up for debate, particularly with such a high economic impact at stake. The problem is that the debate is suffering from a paucity of reliable data.

Were there zero cases of transmission at the Orlando trade show? 10? 100? More?

The crucial issue highlighted by A360 is that it is not possible to have an accurate idea of the potential fallout without follow-up testing — and their transparency about it is a forced product of the public scrutiny around their potentially illegal event. Investigative reporting from the MIT Technology Review strongly suggests that some disclosures might have been prompted by internal pressure from team members who had misgivings about how the event and its follow-up reporting were conducted, and who were prepared to leak information independently.

The only examples of thorough follow-up testing are studies designed specifically to demonstrate the efficacy of pre-event and onsite testing in near-ideal conditions, but the litmus testing so far has been nowhere near as robust.

IN CONCLUSION

These recent outbreaks suggest that while onsite testing improves event safety, it’s far from a guarantee of no risk. Further, without the kind of scrutiny and follow-up testing that goes along with elite events like A360 and high-profile sporting tournaments, the industry can’t make convincing claims of zero onward transmission.

If these events prove anything, it’s that even the most rigorous testing programs cannot stand alone. Consistent mask wearing and social distancing policies may not be possible for players in a hockey game, but these measures need to be upheld at business events. The last thing any organizer wants is for hundreds of thousands of cases to later be traced back to their event through genetic testing — as happened with a biotech event hosted early in the pandemic, before any safety measures were in place.